Corals

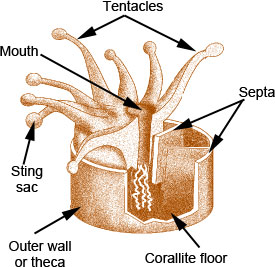

Corals comprise a soft bodied animal (polyp) that lives in a calcareous skeleton (corallum). Food is taken in and waste products are discharged through the mouth, which is surrounded by tentacles with poisonous stings.

The polyp removes calcium carbonate from the sea water to create a skeleton of calcite or aragonite. The cup (or corallite) in which the polyp lives is strengthened by septa (radiating plates), tabulae (corallite floors which build up one on the other) and sometimes dissepiments (small concentrically arranged plates between the septa).

Corals have been found in water 6 000 metres deep, but are most common at depths of less than 500 metres. At these depths, the water temperature may be close to 0 degrees Celsius, but corals are most common between 5 and 10 degrees. Deeper water corals are mainly solitary, although some, such as Lophelia, are colonial and form thickets.

Corals reefs on the other hand, are restricted to the warmer regions of the world's oceans such as the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean. Reef-building corals favour water depths of less than 10-20 metres and temperatures between 25 and 29 degrees Celsius.

Octocorals are rarely found as fossils as they lack a hard skeleton, but many palaeontologists believe that one of Britain's oldest known animals, Charnia, belongs to this group. Faint impressions of this soft-bodied animal have been found in late Precambrian rocks of central England and southern Wales.